- Home

- Joy Rhoades

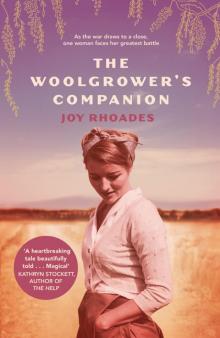

The Woolgrower's Companion Page 2

The Woolgrower's Companion Read online

Page 2

‘I will be clear. You must —’ Addison stopped. ‘Mrs Dowd,’ he said. He looked back at her father. ‘We’ll take this up again, Ralph.’

They watched Addison get into his car.

‘What’s wrong, Dad?’

‘Nothin. Addison’s a drongo.’

Grimes usually drove, but today Ed got behind the wheel, as Grimes stood guard in the truck tray with his back against the cab, the prisoners at his feet. Up close, the two POWs looked sullen and dusty, the younger one with a piece of grass caught in his beard. Canali, the other one, wiped at the sweat on his brow with the back of his hand and stole another glance at Kate.

‘Let’s get going, Ed,’ Kate said, trying to ignore the POW.

CHAPTER 2

As to Australia’s proud place as keeper of so much of the world’s sheep, it may safely be said to spring from the arrival, in 1796, of the first Merino to these shores.

THE WOOLGROWER’S COMPANION, 1906

Kate was glad to be with her father and Harry in the safety of their Hudson. She kept her eyes on the side mirror, watching the Amiens truck as they went through Longhope, past the houses, the pubs and the churches, the stock and station agents and the sapphire buyers. They crossed the dry creek bed that wound through the town like a snake, and then her father turned the vehicle onto the main road running west. ‘Now, off to Amiens,’ he said, settling into the driver’s seat. The drive home was nineteen miles, at least an hour, of mostly straight dirt road, at this time of day directly into the western sun.

‘Harry, you’ll have the time of your life on Amiens.’ Her father was not much of a talker, but for some odd reason he seemed to have taken a shine to the boy. Harry was lost in the bench seat, eyes on the bush spinning by.

‘Four-hundred-odd head of cattle, seven thousand or so sheep. Merinos, all of em. Best wool in the world.’

‘Why’s that, then?’

‘Merino’s the finest. Makes the best cloth. And it’s all Merino in this district. And us? We’ve got a lot of country. Fourteen thousand acres.’

‘A helluva lot,’ Harry said.

Her father laughed. ‘A good bit of dirt, as they say in the bush. Weren’t always, of course. I built her up from a soldier settler block after the First War to the biggest in the district.’

The boy nodded.

In the driver’s seat Stimson smiled. ‘You know, an Abo fella – a stockman – he said to me once, “We don’t own the land, boss.” Well, of course Abos don’t own land. But you know what he said then, this old bloke? “The land owns us. The land owns us.” I think that fella might have been onto something. Amiens? It owns me. Have to look after it.’

In the mirror, Kate saw Harry’s head drop back, resting in the corner between the bench seat and the car door. The drive would put him to sleep, no doubt, after nine long hours on the train from Sydney. The miles went by, Kate’s eyes shifting between her father, the side mirror with the Amiens truck behind them, and the horizon. POWs or no POWs, she liked this time of day, the late afternoon turning the leaves and trunks of the gums pink. These colours leaked into the sky, soft pinks and reds creeping up into the clouds from the horizon as the sun dipped. But with a pink sky, there’d be no rain the next day.

Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight. She’d grown up with the saying but always found it odd. It must have been an English shepherd, a shepherd with too much rain rather than too little. A red sky here made no one happy.

‘Here we are.’ Her father turned the big Hudson off the main road. He slowed the vehicle to a crawl to cross the stock grid, and they shuddered over it, coming to a stop just beyond. ‘It’s land like this, Harry,’ her father said of Amiens, ‘land, or somethin y’can hold in y’hand. Not money in the bank. A bank’ll take your money and pull the rug out soon as look at you.’

Her father put the vehicle into gear. ‘An there’s a lot t’be proud of. Forty-odd-thousand reasons.’

‘Dad!’ Kate looked back. Fortunately, Harry was asleep. ‘Dad, please don’t mention money to Harry.’

He shrugged.

Kate looked out to her right at the dam. At least that was a constant. She loved the dam, even in a drought and even with its history; it had been built when her father had cut off the creeks from the neighbours below. Tonight its surface was graveyard-still in the dusk light, broken only by the bare trunks of drowned trees. As much dried mud as water now, it still ran at least a hundred yards across, and they were so lucky to have that water.

She looked up the hill to the line of bunya pines, the tall evergreen conifers hiding much of the squat homestead. As the car came out of the gully, a lorikeet shot up from the track ahead and then the dogs were upon them, barking and leaping.

Her father brought them to a stop outside the double gates. ‘This is the homestead, Harry,’ he said.

‘He’s asleep, Dad.’

Her father ignored her. ‘She’s got a beaut garden, even in this dry. And a bowerbird. Kate’ll show ya.’

Out of the car, her father stretched and rubbed the base of his neck. Kate leaned over to the backseat to nudge the sleeping Harry awake. The pup, Rusty, jumped up and put his head and paws in Kate’s open window for a pat. Ed thought Rusty wasn’t the full quid but Kate had a soft spot for the pup. She got out and Harry unwound from the car slowly, like a possum from a hole in a tree.

‘What’s that then?’ he said, pointing to a fenced area away beyond the homestead.

‘It’s private,’ Kate said. ‘It’s my mother’s grave.’

He looked again, appraisingly. ‘Big enough for all of yez, eh.’

She was taken aback, until she remembered he’d lost his own mum.

‘What about that?’ Harry pointed again.

‘The meat house. For hanging the carcasses.’

‘You mean a stiff?’

Kate laughed. ‘No, a sheep carcass. Or a bullock. For eating.’

Rusty and the other dogs, Puck and Gunner, lost interest in the men in the truck and came back. Rusty took a sniff at Harry’s privates, and the boy backed away and the pup chased, thinking he was on for a game. Harry was stuck up against the car, the dogs hemming him in.

‘They’re just being friendly,’ Kate said. ‘The pup, the one with the patch on his ear and his eye, that’s Rusty. Puck’s the big one, the blue heeler with the piece out of his tail. The third one’s Gunner.’

Harry stayed put up against the car, his back arched away from the dogs.

‘They won’t hurt you, truly. Let’s get you over to your uncle. C’mon.’

Harry frowned but followed her across to the truck, trailed by the dogs. There Kate nodded a hullo at the two men, Johnno and Spinks – Amiens’ only remaining stockmen – who’d appeared from the yards. They’d worked on Amiens since the war, when the white stockmen had all joined up. Aboriginal men could not enlist, officially anyhow. But that was the silver lining for the graziers. Grimes had them working out in the paddocks or cutting feed and fixing fences, though Kate suspected they preferred to be in the bush by themselves and away from Grimes. She knew she would.

‘That a uniform?’ Harry asked.

Kate laughed. Both lanky, the men were in identical get-ups, ration-issue clothes bought with Amiens’ coupons – the same straight brown dungarees, big-buckled belts, white shirts rolled up to their elbows, and ten-gallon hats.

She glanced across at the POWs. The bearded one, Bottinella, had climbed down from the truck. Canali hadn’t moved, was standing in the back of the tray, looking about with his odd pale eyes.

Harry was staring at the two stockmen. ‘I never seen boongs up close before.’

‘You shouldn’t say that. Boongs, I mean. It’s not nice. Aren’t there lots of Aborigines in Wollongong anyhow?’

‘Nuh,’ he said, his eyes on the stockmen. ‘They cleaned em out years ago.’

Johnno saw Harry staring and came over slowly. ‘You orright, mate?’

‘This is Harry,’ Kate said. ‘This is John

Banning – but everyone calls him Johnno – and Billy Spinks.’

Johnno smiled, a missing front tooth smile.

‘You lost y’tooth,’ Harry said.

Johnno’s hand went to his mouth and worry creased the stockman’s face. ‘Spinksy hit me agin this mornin, eh.’

‘I decked im. I got a short fuse, like ole Grimesy.’ Spinks loomed over the boy and Harry shrank back.

‘Cut it out, Billy. Y’scarin im,’ Johnno said. Billy grinned and the pair of them faded back to the truck.

‘Johnno’s always stirring for a laugh,’ Kate said. ‘Your uncle’ll be finished soon, and then he’ll take you to the manager’s cottage. You want to come with me, for now?’

He followed her across the house paddock and through the white wooden gates. A black chook picked its way up the inside of the house fence. Kate went past it, round the circular drive in front of the homestead and up the short verandah staircase at the side, near the big veggie garden. She had to step over the black-and-white cat lying across the middle rung.

Harry stopped at the cat.

‘That’s the house cat, Peng. Peng for penguin because she’s black and white.’

‘Fat cat. She preggers?’

‘No, no. Just round.’

‘You got kids?’ Harry asked.

‘What? No.’

‘But y’hitched?’

She nodded, feeling the familiar pang of failure. It had only been a few months though, that she and Jack had been together as a married couple, just while his hand wound healed, before he got classed as fit again. He’d taken to her and to the district like a duck to water. Met, courted, married, gone off to fight again, all too fast. But no baby.

Daisy, the Aboriginal domestic, appeared in the kitchen doorway. She was sweet and gangly with a big head, a skinny body and long legs, hidden today in a shapeless brown dress, government issue, a remnant of the Home.

‘Boss want tea, Missus?’

‘Yes. Please. Oh, and Daisy – this is Harry Grimes.’

The girl nodded a hullo but she didn’t look at the boy. Harry ignored her too.

‘Daisy? I’d stay out of sight for a bit, away from those men. You know?’ Kate said.

The girl nodded, frowning, and went back into the kitchen.

‘She a half-caste? Where she come from?’ Harry asked.

‘The Domestic Training Home in town. But she lives here now.’

‘When she see her mum and dad?’

Kate paused. ‘She doesn’t. She’s from Broken Hill, way out west. But she goes to the Mission once a month on a Sunday. For church.’

‘To make up for it? That’s piss-poor.’

Kate’s father came in through the gate. ‘Cuppa tea, Kate? Bet young Harry’d like a bikkie too.’ He didn’t wait for her answer and went up the steps.

Bikkies for Harry, no less. Kate wondered whether she would have to look after this odd little boy.

Outside, Grimes was shifting the POWs. ‘Move out,’ he called. Ed went first and the bearded POW followed along the track towards the single men’s quarters, a chook hurrying out of their way. The other POW took his time but there was efficiency in the way he moved; nothing was without forethought.

‘Come on then, Harry. Let’s get this tea,’ Kate said.

‘Gorn!’ Grimes shouted and Kate looked back, surprised that Grimes would use a command for the dogs on a POW. But it was for Rusty. The pup was chasing sheep, a wether, in the paddock just beyond the house, just for the fun.

‘Git im!’ Grimes shouted again and whistled up the other dogs. They went after the pup and cut him out and away from the sheep. With no dog behind it, the wether slowed to a stop, its fleece brown with dust after months without rain.

Rusty was lucky it had not been a ram he picked on; a ram would have a go at a dog. Kate made a note in her head to tell her father that Rusty might be a chaser. Then she thought better of it – she didn’t want to trouble him. But Rusty had better learn.

A half hour later, Kate, her father and even Harry were seated in the wicker chairs on the house’s eastern verandah, having tea. A blue shirt appeared over the rise from the single men’s quarters: Mr Grimes. When he got close and saw Harry sitting up with his boss, his brows set with disapproval. Kate agreed. There was a strict hierarchy in the bush, and the children of the stockmen, even of the manager, did not take tea with the grazier’s family.

With Grimes just below them on the mostly dead lawn, Kate poured the tea, offering him a cup by convention. He, in turn, shook his head.

‘We’ll take the Italians out first thing tomorrow so they get the lay of the land,’ her father said, a booted foot jiggling as he spoke. ‘Get em into the routine – checkin fences, cuttin feed for the sheep and for the cattle, too.’

Grimes said nothing, his eyes on the boy in the verandah chair above him.

‘Got em settled in at the quarters?’ Her father stirred two spoons of sugar into his tea and reached for one of Daisy’s scones, spread with a little precious butter and some jam.

‘Yeah. Ed’s camped out up there to keep an eye on em, with a shotgun. But I tell you, I reckon —’ Grimes stopped and frowned at Harry as he licked the butter and jam off his scone.

Kate was distracted by her father, who was scratching hard at his groin. ‘Dad,’ she urged, a half-whisper, and he stopped.

Grimes either hadn’t seen it or chose not to. ‘Anyhow, I reckon we need a few more blokes up there tonight. In case they go on the run.’

Her father laughed. ‘Where they gunna hide? Here?’ He waved a hand out across the property, its miles of bare paddocks.

‘That first fella? Canali? Don’t turn y’back on im. An they might come after us, if you get my drift.’ Grimes looked at Kate. ‘She should know how to use your revolver, boss.’

‘I’m tellin ya. Not dangerous.’ Her father was starting to get annoyed. He stood up, brushing the crumbs off his hands at the edge of the verandah.

Grimes changed tack. ‘Another thing, boss. I need the cheque for the men’s pay.’

‘What?’ Her father was distracted, still annoyed.

‘It’s Friday. Payday.’

‘I’ll get the cheque-book,’ Kate said. She ran to the kitchen, got the cheque-book then put it down, open, in front of her father. She held out a pen. ‘I can write it if you like,’ she said, reaching for the book. She’d seen him do it. ‘I make it out to Cash, don’t I?’ She went ahead, finding the amount of the previous week’s pay on the stub and writing the figure well clear of the Amiens Pastoral Company signature line. He signed and she handed the cheque down to Grimes on the lawn below. He slipped it into the breast pocket of his shirt.

‘Orright. See ya at first light, then. C’mon, Harry.’ Grimes put his hat on and went.

The boy stood up but stayed put, with one small hand on the armrest of the wicker chair.

‘C’mon.’ Grimes’s tone was brusque from the gate. Harry grabbed an extra scone on his way and ran to follow his uncle’s march across the flat. He caught up and fell in, and blew raspberries in time, one for each step marched, until Grimes gave him a filthy look and Harry stopped.

Inside Kate could hear Daisy in the kitchen, the clang of a saucepan. She tried to think of a way to ask her father about Addison and the bank. But they sat, silent, in the dusk. A flash of green and blue caught Kate’s eye over the drive. A rainbow lorikeet swooped across from the big Californian pine to join two others in the black-branched wattle by the side gate. On the fence line with the stringybark paddock something moved. A rabbit, foraging.

‘Bit prickly,’ Kate said to her father. ‘The boy Harry, I mean.’

‘Mebbe.’ Her father rubbed his hand backwards and forwards over the salt and pepper stubble of his short back and sides. ‘He’s had a bad trot. Which reminds me,’ he said. He got up and went along the verandah and into the office, boots and all. Boots came off at the door in the bush; it was universal in homesteads in case dirt or spiders or ticks

were onboard. But her father was forgetting now, sometimes.

She could hear him shifting things about in the office. ‘What are you looking for, Dad?’ He reappeared carrying her old draughts box and a dusty jigsaw puzzle, a map of Australia. ‘You want to play?’

He grinned, blowing dust off the top of the draughts box.

‘You used to let me win, Dad.’ She smiled. ‘All the time.’

‘Well, they’re not for you. For Harry. He can do the puzzle on the end o’ the kitchen table.’

She tried not to be annoyed, about the kitchen table or about Harry. They sat in silence for a time, with the soft backdrop of Daisy moving about in the kitchen. Kate needed to get on with it.

‘What did Mr Addison want today?’

‘What?’ Her father studied the draughts on the board.

‘Mr Addison. From the bank.’

‘Nothin. Had his facts wrong.’ He stood up and went inside, boots on, leaving the games.

Kate stood too and hurled the dregs of her tea onto the lawn, aiming for one of the yellow clumps. By now, the sky had turned a deep pink as the last of the sun slipped behind the blue-black of Mount Perseverance, right on the edge of Amiens. Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight. Pommie bastard shepherds, her father would say. She stacked the cups and saucers onto the tray and went in. She needed to find the keys. They never locked the homestead doors, but she would now.

CHAPTER 3

While boldness in a ram may portend vigour in its offspring, belligerence means danger for all.

THE WOOLGROWER’S COMPANION, 1906

Just before half past six the next morning, Kate and her father sat at the kitchen table eating their way through a wordless breakfast, the plip-plop of Daisy’s shoes against the lino the only sound in the house.

‘You wan another chop, Missus?’

Kate shook her head, her mouth full.

‘Daisy’s the one who should have the damn chop. Skin and bone.’

Kate looked hard at her father. Embarrassed, Daisy turned away to the sink. She was only fourteen. But she was skinny, as skinny as the POWs – that was the truth, no matter how much Kate encouraged her to eat. She hoped the girl wasn’t still pining for her family.

The Woolgrower's Companion

The Woolgrower's Companion