- Home

- Joy Rhoades

The Burnt Country Page 2

The Burnt Country Read online

Page 2

The stack of mail caught her eye, a handwritten letter addressed to Daisy on the top.

‘Any chance of a scone?’ Maguire asked, watching her.

‘Sorry,’ Kate said, not sounding sorry. ‘Bit early today. Mrs Walters hasn’t had a chance.’ Maguire should count himself lucky. Mrs Walters had many good points. Cooking was not one of them.

‘So ya gettin that yard-rail fixed, Mrs D?’ Maguire asked.

‘What’s that?’

‘The yard-rail. Mebbe you could borrow that Eye-tie, Luca Canali, from the Rileys t’fix it.’

Kate didn’t react. Maguire had tried that trick on her before, in the months since Luca had been back in Australia. She’d been shocked when she first heard that he had returned. It could only mean that there was no family in Italy to keep him there. No one left. She grew horrified, too, that he may have come back for her, and shaken that Luca could still move her.

‘He’s a handy bloke to have about the place, isn’t he?’ Maguire grinned, trying again. Kate smiled politely.

She still hadn’t heard, but half hoped that Luca had brought a wife with him from Italy. Many of the former POWs had done so when they came back. But that thought palled and she was relieved he hadn’t tried to see her. A swirl of emotions, of wistfulness and denial, still plagued her, but now at least she was better at putting on a poker face for Maguire.

The postman was watching her closely. ‘The rail,’ Kate said. ‘Ed’s fixing it.’ Ed Storch, her head stockman, would have it fixed too, if it had ever been broken.

‘Hey Dais, how is Ed, anyhow?’ Maguire grinned as Daisy fled, embarrassed, to the laundry.

‘Any bread for us today?’ Kate asked, wanting to shut him up. That sort of ribbing was dangerous. To look at, Ed passed for white. But there was gossip that he was part Aboriginal. And no self-respecting white man would fall in love with an Aboriginal girl.

‘No bread t’day. The oven’s had it, ’parently. They waitin on a new element from Armidale.’ Maguire drained the last of his tea and put the mug on the sink. ‘You had any rain?’

‘Not this week,’ Kate said. ‘Still, I count my blessings after this run of good seasons.’

‘Yeah, well. This sort of pasture means fire, sooner or later. You people are burnin off?’

Kate paused before answering. ‘A bit.’

‘That’s what I hear, round and about.’

Kate knew Maguire’s mail run took him all over the district, including to her difficult neighbour, John Fleming on Longhope Downs. She was casual when she spoke. ‘We back onto the State Forest. And we do nothing out of the ordinary in the way of burning off.’

‘Is that right?’ Maguire wasn’t convinced, and his was probably Fleming’s view. ‘Better not let it get away on youse, eh.’

Kate watched the big postman saunter back across the lawn to the mail truck under a bright blue sky. She would warn Ed that there was talk in town about the unusual burning off on Amiens. He’d need to be ready if someone had a go at him over it, in the street.

She put that out of her head; she needed to get to the yards and went to get a hat. But back on the verandah, as the truck went down into the gully, she saw a police car pass it and come on towards the homestead.

‘Daisy!’ Kate called urgently into the kitchen.

‘I seen im, Missus,’ Daisy said. With Pearl in her arms she ran through the laundry and out the back door, her flight hidden by the trees along the house paddock fence. Heaven only knew what Mrs Walters would think of that. But it was necessary. The sergeant, among other things, was the representative of the Aborigines Welfare Board for the district.

Yet what if Daisy and Pearl weren’t the reason for his visit? Had something happened to Jack overnight? Kate dismissed that. Maguire would have known. Maguire would have also seen the police car, and it would be all around the district soon, that the police were at Amiens.

The sergeant got out of the car and put his hat on, trapping his large ears. He was known as Wingnut on account of those ears, and Kate always had to think hard to remember his real name. Withers, that was it. At least he was alone. In her experience, he brought reinforcements for arrests and for serving court papers. She waited on the verandah, working to stay calm.

CHAPTER 3

Mouthing is a means by which a sheep’s age may be immediately established. For decrepitude sets in, from just four years of age, on dry, harsh pastures, manifesting itself in gaps and falling teeth.

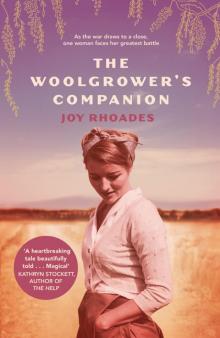

THE WOOLGROWER’S COMPANION, 1906

Kate still felt odd going into her father’s office. Her office, now. But it was private, and that’s what she needed today for the policeman. She led Wingnut into the cool of the room and shut the door, keeping Mrs Walters out of hearing.

The visitor’s chair creaked as Wingnut sat, his hat in his hands, his ears free. She sat too, facing him across the old desk, its big top bare apart from her much-thumbed guide to woolgrowing, The Woolgrower’s Companion, open where she’d left it.

‘All well, Mrs D?’ Wingnut looked closely at her bruised cheek.

‘Oh,’ she said, making herself smile but wincing instead with the pain. ‘A yard-rail came down on me.’

He nodded; like Maguire, not buying that. ‘I see you got the Companion.’

Kate wondered when he’d get to the point. She’d been looking in vain for anything on preparation for bushfire. There was a lot on what to do after a fire. Nothing else. And she was embarrassed in case Wingnut thought she needed to study. ‘Can I get you some tea?’

‘No. Thanks. I won’t stay long. I come about the Board. They been onto me from Sydney. Daisy’s gotta give up Pearl.’

Kate held her breath as he went on and on.

‘They’ve had enough, Mrs D. Daisy’s an unmarried half-caste, with a toddler born out of wedlock. She’s gotta give up that child to be brung up by a white family. It’s Board policy. She shoulda give her up at birth. As you know.’

Kate did know. Wingnut had told her often enough. If Pearl had been born in hospital, she would have been taken by the Board then. Daisy too would have been transferred to another employer, away from Kate and from her baby. Instead, Daisy, heavily pregnant, had absconded and made her way to Longhope and to Amiens, where Pearl had been born. Kate and Daisy had spent the three years since trying to fend off the Board.

Wingnut sighed. ‘You’ve heard this said before, Mrs D. The Board says for the good of the child, it’s gotta be raised right.’

Kate started to protest but he held up a hand.

‘I know youse are doin a good job. But rules are rules. The Board’s tellin me now either you deliver Pearl, or they’ll transfer Daisy to another employer – one or the other, by the end of the month.’

Kate stared at him.

‘End of the month, it is.’ He nodded. ‘I think ya stirred em up with that wages nonsense, if ya don’t mind me sayin so.’

Kate looked down at her hands. ‘I shouldn’t have mentioned it. But Daisy got that letter, saying that they still hold money for her. I just asked for it.’

‘They lookin after it, Mrs D. For all the Abos. Not just Daisy. That’s their job, eh. They don’t take kindly to people poking into their business.’

Kate wished she’d never raised the damn wages.

‘They’ve been pretty patient, what with your father passing away and so on. But that was three years ago.’ Wingnut stood up, turning his hat in his hands. ‘Righto.’ He saw the gun-rack on the wall, and its padlock. ‘Good that you keep it locked.’ His voice was soft, sympathetic.

‘I had it put in, you know. After—’

‘Your father’s accident,’ he said.

‘Yes.’ It had been Wingnut who’d determined that her father’s death was accidental when he was ‘cleaning his gun’, although both of them knew otherwise. The district knew too.

‘The trick is to hide the key from Harry,’ Kate said.

She saw Wingnut out then. He strode across the lawn, startling Donald.

The wallaroo bounded away in fright from the stranger. But it was Pearl Kate thought of, and worry wormed its way in. Kate and Daisy seemed to have run out of options.

At a brisk pace, you could make it over the hill from the homestead to the yards in only six minutes. Harry had timed it once. As she went, Kate watched where she put each booted foot on the track. Mating season for snakes was over, but that didn’t mean she could avoid a bite if she trod on one.

Kate walked fast, not wanting to miss John Fleming or his man coming for the sheep. She needed the cheque, and she needed to get it to Addison. The bank manager had approved the sale of this stock, on condition the cheque was banked, of course. She’d made that beginner’s mistake only once, forgetting to get his OK, forgetting that the stock, like the land, was mortgaged to the bank. Most graziers just sold and told the bank after. But Addison had a long history with Kate; he was another one who refused to believe a woman could run the place. He used any means he could to threaten her with default. It was wise, then, always to get his approval first to sell her stock.

It was a glorious morning: that bright sky and some clouds so wispy they’d come to nothing, rain-wise. Birds shrieked from the ringbarked tree that stood like a dead sentinel by the gate, its trunk smooth and grey with age. A flock of galahs festooned the bare branches like Christmas decorations. Her mother had loved them, these beautiful birds, with their pale crests, dark pink breasts, and grey wings like a cloak over the top. They watched as Kate walked by, squawking at her like men propping up the bar at a pub in town.

The bird noise receded behind her, soon replaced by a dusty air full of bleated thirst and hunger, the smell of dung and urine. The sheep had been yarded since the night before, to empty out, ready to be trucked today. Water and feed waited for them at their new home.

‘Mornin, Mrs D.’ Ed, her manager, smiled a greeting at Kate, his eyes stopping on her bruised cheek. He said nothing. Daisy had probably told him. He was a good egg. They were about the same age, she and Ed. Together they’d somehow managed to keep Amiens afloat since Kate’s father had died.

Ed manoeuvred his gammy leg between the rails and stepped neatly into the yards. He’d hurt one leg as a kid, rolled on by a horse he was breaking, but he compensated somehow. Put him on a horse and you’d never know. Kate was forever surprised by his agility.

‘They ready for truckin,’ Ed said. He moved through the throng of sheep, arms out a bit in case of a knock, and also to pat a sheep’s head, scratch its ear. He loved ‘his girls’. ‘Maguire been this mornin?’

‘Just left. There’s talk in town about us doing too much burning off.’

‘Yeah?’ He sounded annoyed.

‘My thoughts exactly.’ Every grazier who was any good burnt off. But Amiens’s process was a bit different. Their very methodical approach had been Ed’s quiet idea, way back, as soon as the drought broke in ’45 to ’46 and the good pasture came on. She wasn’t sure how he knew about fire but suspected he was taught as a boy, growing up on a place outside Wilcannia, not far from Daisy’s home of Broken Hill.

Burning off generally just made sense. No area got too overgrown, and that prevented a build-up of fuel, so a bushfire might be slowed or even stopped.

Most local graziers were sensible about the fire risk, but not many went about it as often or as carefully. Some, the worst, were all-or-nothing types. They’d have big, infrequent, widespread burns, and those graziers had long since stopped those. Others, the more prudent types like Kate, were still doing small patches. They chose where and when carefully. Neat. Methodical. Controlled.

She looked off towards the State Forest with some satisfaction. Up to that boundary the pasture had not been allowed to build up or get unmanageable. Kate suspected she was being singled out for criticism for the usual reasons. She was a woman. What did she know about burning off, or sheep for that matter? And her father, never an easy man, had made enemies in his lifetime. Small towns have long memories. Some visited that ill will on Kate, when they got the chance.

‘Did ya hear Grimesy’s back? Fleming’s hired him as manager, ’parently.’

‘Manager?’ Kate looked at Ed across the platform of sheep backs. ‘What about Mr Tonkin?’

‘Word is Fleming told him he could lump it or walk.’

An unhappy thought occurred to Kate. ‘It won’t be Grimes today, will it? Coming for Fleming’s stock?’ It was common knowledge in the district that after her father died, Grimes didn’t like working for Kate so he’d quit. And she was worried about Harry.

‘We’re bout t’find out.’ The Flemings’ truck was visible now on the track in from the main road.

‘Even if it’s Grimes, he’ll still have to pay,’ Kate said. ‘I mean, it’s Fleming.’ She needed that money. They always needed money. And Fleming, oddly, was known around the district as a slow payer.

The truck pulled up, the man’s hat making it hard to see his face. But then out of the cabin, at a leisurely pace, came Amiens’s former manager, Keith Grimes. Kate’s bruised cheek throbbed.

She’d forgotten how tall he was – over six foot – and broad, solid from a lifetime of hard yakka. Grimes’s thick eyebrows were more white than grey now, and he clearly still liked his blue work shirts. He reminded Kate of her father – they’d been the same vintage – and suddenly she missed him. He could always handle this man.

‘Mornin,’ Grimes said. ‘Took one to the mouth, Mrs D?’

The heat went to her face and her lip throbbed. ‘It was an accident.’

‘That a fact?’

‘You’re working for Fleming,’ she said flatly. If he was not to offer pleasantries after years away, then neither would she.

‘Yup. I’m here to get his wethers.’

They’re not his yet went through Kate’s mind.

‘How ya been?’ Ed called from inside the yards.

Grimes ignored him.

‘Pretty good. How you been, Ed?’ Ed parroted the reply that should have been given, gently needling his old boss.

But Grimes just approached the yards and climbed in.

‘If you back her up t’the ramp, I’ll load,’ Ed said.

‘I’ll see em first.’

‘Woddaya mean?’

‘Gunna go over em. Can’t trust any old bloke these days.’

They half thought he was joking. But to make his point, he caught a wether, forcing open its mouth to inspect the teeth. Satisfied with that one at least, he moved across the yards towards the drafting race, where he could check them one by one.

By insisting on checking the stock, he was implying that Kate and Ed would include ring-ins – a few lame, old or poorly animals – with the rest. The bloke business was a dig at Kate. Grimes had hated working for a woman, even the woman who owned the best Merino flock in the district.

The next wether shook its head unhappily, as Grimes counted its incisors to check the age. Kate hoped one of them would give a good nip to his hand.

‘Get em organised,’ Grimes called to Ed, issuing the orders.

Ed’s face set and Kate’s with it. Grimes meant to check every animal. Kate knew she should refuse to sell at all, cheque or no cheque. She should. But they needed the money.

Ed whistled up the dogs and started the long process of putting the wethers, one at a time, into the race for Grimes to examine.

‘Be a while, Mrs D,’ Grimes said without looking up, dismissing her. ‘I’ll come to the house on m’way out.’

Bastard was what her father would have said. But then Grimes would never have done this to him. Kate stalked back to the house, her boots throwing up tiny breaths of dust on the track. She was angry with herself for being rattled by Grimes, but glad that Harry was at school. She and Ed might withstand Amiens’s former manager, but Grimes and Harry together were combustible.

CHAPTER 4

The woolgrower shall be mindful that quiet demeanour and good temper are worthy traits of rams and ewes. A beast of true value does not possess virili

ty or strength of line alone.

THE WOOLGROWER’S COMPANION, 1906

As Kate walked in from the yards, she could see Mrs Walters in the homestead garden under the clothes line. Cross as Kate was with Grimes, she knew she had to speak to the new housekeeper about Jack. Kate’s calm persuasion was needed.

Mrs Walters was hauling damp white sheets onto the lines in the hot breeze. She was a slight thing, no more than five feet two, and had to stretch up to peg. She reminded Kate of a wallaroo, compact and industrious. Kate had made the mistake of mentioning that to Harry, when Mrs Walters first arrived. Harry hoped that Mrs Walters wouldn’t deposit piles of manure everywhere in the garden, like Donald.

Kate took one end of an unruly sheet and helped haul it up over the line, trying to get up the gumption to say something. The previous housekeeper hadn’t lasted a week, shocked at what she found at Amiens. An absent husband, a half-caste child, gossip about Kate’s father’s death. And she hadn’t even suffered a visit from Jack.

This time, with a new agency, Kate had tried the other tack. She just got Mrs Walters up from Sydney on the train and would let her work all that out. Mrs Walters, a widow, needed to support herself, and in the ten days she’d been with them, she seemed to have accepted the circumstances. Until Jack’s visit.

‘It’s warm for this time of year,’ Kate began.

‘Yes?’ Mrs Walters kept pegging. A sheen of perspiration shone on her face in the heat.

‘The old-timers will tell you a hot November brings a dry summer out here.’ Bushfire too, only Kate didn’t add that.

Overhead, a family of lorikeets screeched and swooped. Daisy’s lorikeets; she loved their noise and colour.

‘I’m very sorry, Mrs Walters, about last night. I’m sorry I didn’t tell you.’ The small woman frowned, and Kate hurried on. ‘He – my husband – doesn’t live in the district. He’ll be gone soon. Back to the Islands. To his work there.’ The words came out in a rush. Last night had shaken Kate too. The woman kept pegging, unmoved. ‘We need you, Mrs Walters. Very much.’

The Woolgrower's Companion

The Woolgrower's Companion