- Home

- Joy Rhoades

The Burnt Country Page 3

The Burnt Country Read online

Page 3

She stopped pegging then and hugged a damp sheet to her like a child. ‘Can I ask you about Pearl, Mrs Dowd?’

Kate looked off towards the horizon and the weary pasture. ‘She’s my half-sister.’

‘Your father’s child.’ Mrs Walters’s voice was soft.

‘Yes.’ It had been so hard once to say that. ‘But he. My father. He – Daisy didn’t want—’

Lips pursed, Mrs Walters shook her head and dropped her eyes to the sheet in her arms.

Kate waited for the outrage, for the I can’t stay under this roof a minute longer speech. The previous housekeeper had been shocked that Kate would acknowledge a black baby sister. That was the line that Longhope took too, that Kate was foolhardy, unhinged, even, to embrace Pearl as family. Deny the rape, deny the child. Why hadn’t she done that? they thought.

Kate sighed, remembering the awfulness of that time, and worse, the shunning since. People were not uncivil in the street of Longhope. They’d nod. But no one stopped to speak to her. Now, she had only the Rileys, and her own people on Amiens.

Suddenly, the housekeeper went back to pegging. ‘It’s all right, Mrs Dowd,’ she said, her eyes on the sheet.

‘Really?’ Kate could not believe her luck.

Mrs Walters nodded, a bird-like twitch. ‘But there’s something I must tell you. I wasn’t truthful.’

‘Oh?’ Kate probably wouldn’t mind, so long as Mrs Walters stayed.

‘On the application form. Next to religion, I put Church of England. But it’s not true. I’m Catholic, you see.’ Mrs Walters’s face grew pink. ‘I didn’t think you’d give me the job, since I live in the house with you.’

Kate was confused. While it was worrying that Mrs Walters had lied, it wasn’t such a terrible one. Catholicism was an affliction Kate could handle. ‘That’s all right. You’re here now.’

Almost heady with relief, Kate walked across the lawn to the house. Mrs Walters was staying. One problem solved.

Her relief did not last long. She found Daisy in the kitchen, tears in her eyes, that letter in her hand. ‘Missus—’ Each time Daisy tried to speak, her voice caught. She held the letter out to Kate. ‘Please.’

The letter, in a neat, round hand, was from Daisy’s mother in Broken Hill.

I hope you are safe and good.

I am very sick. The doctor says I only got one month.

I am longing to see you my Daughter. I am waiting for you to come soon.

Kate read the letter again, her heart breaking for Daisy and for her mother. ‘I’m so sorry. You must go to see her, as soon as you can. We’ll pay for your train ticket. Don’t worry about that.’

‘Pearl, Missus? Who look after her?’

‘We’ll manage. Truly. Between Mrs Walters and me.’

‘Wingnut come, Missus?’

Kate paused. ‘He says there’s a time limit the Board has set. The end of the month.’

‘Me or Pearl, eh?’

‘Yes. But we’ll think of something,’ Kate said.

Daisy nodded, unconvinced. Afraid.

Outside a dog barked, as a truck pulled to a stop and its engine was shut down.

Kate frowned. ‘That’ll be Grimes.’

‘Mr Grimes, Missus?’ Daisy asked, alarmed.

‘Yes, he’s back. Stay inside, all right? Keep Pearl out of sight too, won’t you?’

Kate was thinking of what had happened a few weeks before. A visiting mechanic had come to the homestead to be paid. But while Kate was inside getting her cheque-book, Pearl ran onto the verandah. This awful man had sworn at the toddler, and told her to get out, not realising she lived in the homestead. With Pearl crying in Daisy’s arms in the laundry, it was all Kate could do to even pay the man. Grimes would be worse. He knew Daisy, and of Pearl’s birth.

‘I’ll have to go and speak to him.’ Kate touched Daisy’s hand lightly. ‘But we’ll talk again about this. All right? I promise. We’ll get things organised.’

Daisy sniffed the air. She went straight to the stove and pulled the door open. A breath of smoke wafted across the kitchen from Mrs Walters’ cooking. As Kate went out onto the verandah, Mrs Walters passed her, going the other way at speed. It occurred to Kate that perhaps Daisy should take care of the cooking, and Mrs Walters might do the cleaning and laundry. An easy dividing line. Kate suspected this housekeeper would not baulk at Daisy cooking. Some households forbade their Aboriginal girls from touching or preparing food, but Kate had dropped that years before.

She went out as Grimes came up the verandah stairs, and could not help but think of the last time he’d stood there, when he’d quit all those months before. Kate had been more than pleased to hand over his wages and see him go. But today, he had her money.

‘The cheque, please, Mr Grimes.’

‘You people still short of a quid, Mrs D?’

‘The cheque,’ she said again. Kate would not be rankled.

The smell of burnt scones wafted out from the kitchen. ‘Somethin on fire? I hear there’s a bit of that out this way.’ He laughed.

Kate frowned. ‘Careful and often is how we burn off. No cause for alarm.’

Now Mrs Walters came onto the verandah. ‘Shall I get the gentleman some tea, Mrs Dowd?’

‘He’s not staying.’

The housekeeper retreated inside.

Grimes looked out across Amiens’s hills. ‘Bloody Canali’s around too. But I reckon ya know that.’ He smiled. ‘The Eye-ties. Good to hear they shipped that Buconti fella back though. The commie. One down.’

‘The cheque, and then you will leave,’ Kate said firmly. She was annoyed; this cheque business was underhand.

‘Hold on, Mrs D. I come to talk business with you.’

‘Give me my cheque.’

‘Don’t have it. You’ll have to ask John Fleming. It’s his money.’

‘Good day, Mr Grimes.’ Kate headed for the kitchen.

‘I need to talk t’ya bout Harry,’ Grimes said to her back.

Kate turned in the kitchen doorway.

Donald chose that moment to hop round the corner of the house. He stopped on the lawn and looked up at Kate and the visitor.

‘Harry should be with family,’ Grimes continued.

Kate doubted very much that Grimes cared anything about family. He just wanted to get at her. ‘I’ll let him know you were here,’ she said.

‘Let im know? No, Mrs D, the boy’s comin to me and that’s final.’

‘He won’t want to live with you. He never did.’

‘I’m his uncle.’

‘Great-uncle,’ Kate corrected automatically.

‘I’ll come back here with the coppers. With the sergeant. I will, I’m tellin ya.’

So. Grimes was serious. ‘This is not your decision,’ she said.

‘It’s not bloody Harry’s, if that’s what ya thinkin.’

Kate was silent.

‘Righto. I’ll be back with Wingnut.’ Grimes went for the steps.

‘Harry’s grandmother is the person who should decide,’ she said.

‘What?’

‘Mrs Grimes. She should decide.’

He mulled over her suggestion.

‘Well?’ Kate said, sensing her advantage.

‘All right.’ Grimes planted his hat on his head and marched across the green lawn.

From what Kate knew of Harry’s grandmother, she was a practical woman. Four years before, when she’d been too elderly to care for Harry, she’d rung Amiens looking for her brother-in-law. Kate’s father had answered the phone. Without consulting Grimes, Kate’s father had agreed on the spot to take Harry. So Harry came to live on Amiens.

But it was Kate who’d ended up caring for the boy. He’d spent almost all of his waking time at the homestead with her and Daisy, not at Grimes’s cottage. When Grimes had quit and left the district, trying to take Harry with him, the boy absconded and returned to Kate.

What Grimes didn’t know was that Harry had been writing to his grandm

other once a month for the years he’d been gone. After all those letters of happiness, there was no way Mrs Grimes would make Harry leave Amiens now.

CHAPTER 5

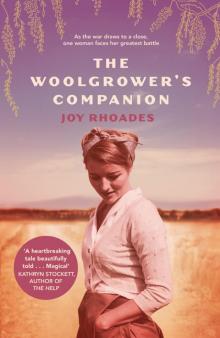

Although unfashionable amongst the less discerning, it is this writer’s firm belief that the demeanour of the woolgrower has an exceptional influence on those about him and is duty-bound to show a deep interest in all who claim the patronage of the holding.

THE WOOLGROWER’S COMPANION, 1906

‘Tony’s made the first eleven, eh. For the district.’ Harry announced the news at the end of the kitchen table, through a mouthful of one of Daisy’s scones. Mrs Walters had ceded the day’s baking to her.

‘What’s that?’ Kate was distracted, still thinking about Grimes’s visit. She had to tell Harry somehow.

‘I’m a better batter. Yet bloody Tony got in the team.’

‘No swearing,’ Kate said, pouring herself a cup of tea. Behind her, the two-way radio squawked, and she listened with half an ear. It was the Rileys’ men. Not Amiens. Ed had found a set of ex-Army two-ways just after the war. He’d talked her into buying them, and she couldn’t imagine how they’d cope without them now. One at the house, one at Ed’s – the manager’s cottage – one at the shed and one in the truck.

‘He couldn’t hit a cricket ball with a shovel.’

Cricket. Harry was talking about cricket. ‘You’ll get in sooner or later, Harry. I know you will.’ She looked at his hair. ‘Are you wet? Did you swim on the way home?’

‘Mebbe. Mebbe not.’

She touched his hair. ‘Wet.’

‘Greasy.’

‘You can swim. But you must promise me you won’t swing off that dead tree. It’ll come down for sure.’ The tree had died soon after the dam filled, its roots drowned.

Harry extracted a shiny green box from his school case.

‘Gosh! Is that a Meccano set? Who gave you that?’

Harry smiled, proud of gift and giver. ‘Luca.’

‘Oh.’ Kate turned away.

‘It’s the bee’s knees. Bit puke green though,’ Harry said. He opened the box on the kitchen table and began to place piece after tiny piece in neat rows.

Daisy frowned. ‘Gunna make the tea there, eh. Verandah, mebbe?’

Kate saw her chance. ‘Tell ya what, Harry. You want to come to the dam paddock with me? Ed’s started to shift mobs in towards the shed for shearing.’

He was up in a flash, any homework forgotten. Harry would have to handle the news that Grimes wanted to raise him, so Kate could live with unfinished homework.

They went out the gate, careful to shut Donald in and keep the dog out.

‘What you doin, Gunner? Ed’ll have your guts for garters if he finds out ya not workin.’ Harry roused on the dog. Gunner loped round them on the short walk to the vehicle.

Kate climbed into the car and fired up the ignition. As they drove, Harry asked, ‘Why they startin so early? Shearin’s not for a coupla weeks.’

She slowed the car to shudder over the grid, out of the house paddock. ‘You know that Amiens is long and thin. So it takes a bit of manoeuvring to get the mobs in from the ends.’

‘Can’t ya walk em in? They’d do it in no time.’ A crow watched them from a ringbarked tree as the car passed.

‘It’s a bit of a risk, to try to get them in, with no time to spare. Because if the temperature’s up – like it is at the moment – they can’t walk as far or as fast in a day. There has to be pasture and water for them too, till shearing.’

‘The dam paddock’s gotta lot of both, eh. Water and grass,’ Harry said.

‘Yes. But we’ve got a lot of mobs to be moved in, in time. We can’t mix mobs without messing up the blood lines.’

‘Tricky.’

‘It’s like a big puzzle, where you can only move one piece at a time—’ Kate began.

‘And that has to be empty, anyhow, to move em into?’

‘Exactly.’ Kate loved talking sheep with Harry. Loved teaching him.

‘Tony reckons there’ll be a lotta bushfires this year. Big ones, his dad says.’ Harry nodded at the rolling hills of yellowed pasture that was now Amiens.

Kate tried to think how best to raise the news about Grimes. Harry had had such a rough trot in his life: he’d lost both parents. Grimes, the only relative able to take him in, was a rotter.

‘Tones is jealous of my Meccano.’

‘That’s a generous gift, Harry.’ Kate tried not to think about Luca. It just made her sad.

Harry produced a smug half-smile.

‘Did you say thank you?’ Kate asked.

He grinned at her. ‘Nuh. Mebbe Thursday. Mrs Riley says I can visit the pups on Thursdays. After school.’

Kate remembered that a litter of puppies had been delivered a month before to one of the Rileys’ work dogs. Mrs Riley was the owner, with her husband, of a stud called Tindale. A lovely couple, older, in their forties, they had no children and a soft spot for Harry – and Luca. They’d sponsored him to emigrate from Italy. Luca and the puppies were a powerful magnet for Harry.

‘Old Luca, eh?’ Harry said, watching her.

She kept her eyes to the front as she drove.

‘You keen on Luca, Mrs D?’

‘No, Harry. Not at all.’ She sounded tired. She was tired.

‘I reckon he’s sweet on you.’

From Harry’s voice, she knew he was grinning. Fighting a weird burst of pain and pleasure, Kate swallowed, and focused on the dam wall on the far side of the paddock. ‘I’m married, Harry,’ she said. It came out sounding hollow. ‘I’m married,’ she repeated, more forceful this time, glancing across.

Harry looked left then right, like Charlie Chaplin. ‘Where’s your old man, then?’ He laughed.

Kate brought the car to a halt at the bottom of the dam wall, and Harry got out, still grinning.

Had Luca said something to Harry? She hoped not. Poor Luca, if he still felt anything for her, if he thought that there was a chance for them. Not now. That was long dead. But she wasn’t surprised in some ways that he’d come back. He always had drive, wanting to make something of his life.

They walked together, she and Harry, towards the dam wall, but Kate’s mind was still on Luca. She had loved him, that she was sure of. But after the war, after he was shipped home and as time passed, she wondered more and more how it had even been possible. How could she, a married woman then and still, have allowed herself to fall in love with him? Ashamed, she’d done her best to work Luca out of her head and her heart, making herself imagine him in Italy, married with children, doting on his family. Painful, but necessary. Duty came first.

Because in those same postwar months and years, Kate began to understand just how hard the Aborigines Welfare Board would fight to separate Daisy from Pearl. She realised that she’d have to be devoted to both mother and child to help them at all. Her father’s terrible rape of Daisy had decided Kate’s duty and her future.

After the war, when Jack came back, he’d wanted them to sell Amiens and move to the Islands, to escape the shame of her father’s suicide. Pride and his good name had always been everything to Jack. But Kate could not take Daisy or Pearl with them to the Islands; the Aborigines Welfare Board would never allow it and they’d snatch both, sending them, apart, to some unknown and difficult future.

So Kate said no to Jack. He could not believe it. But for her it was easy. Yes, she was a bad wife to him. That was true. But now she had to look after Daisy and Pearl, and Harry as well. Jack had said, I have to look after myself? She’d shrugged, immovable, but secretly afraid in the face of his anger.

Hopefully Jack was gone again, back to the Islands, at least for now.

She followed Harry up the dam wall towards the general direction of the dust, the bleating of the mob, the shouts of men and dogs barking.

Kate and Harry stood on the top, looking across the spread of the dam water to the men and the mobs beyond. Kate loved to watch them shift stock, a remarkabl

e flow of linked pieces, like a flock of birds, separate yet connected, wheeling and moving with their brethren.

‘A murmuration, my dad called it,’ Kate said, her eyes fixed on the movement of the stock, the mob turning as one as the stockmen forced them this way, then that, towards the gate.

‘A murmur-what?’

‘Murmuration. Birds and fish do it. Dad reckoned sheep do it too. Swarm behaviour.’

But Harry wasn’t impressed; he was looking at the dam water. ‘Can sheep swim?’

‘If they have to. If there’s a flood or they fall in or something.’

He considered that. Harry’s curiosity was a good thing, Kate reminded herself. He wanted to learn. Amiens might be his one day. Pearl popped into Kate’s head. What about Pearl?

‘Miss Parkin told us camels can’t swim. But I reckon that’s bull dust. Armadillos can’t though.’

Kate was hard-pressed to know what an armadillo looked like. Armour, she guessed. It was probably heavy.

‘Why don’t you help at the gate?’

Harry ran down the dam wall and off across the paddock, to duck through the fence wire. Part of the mob was through, with a bit still to come. They’d want to be one flock, at the end of the day.

Kate waved a hello to Robbo, the new stockman, on horseback on the other side of the fence. He touched his hat but looked away. They’d been peers of a sort, both progeny of local graziers, but when Robbo came home from the war, the father and son had fallen out badly. Robbo had trouble holding down a job so, despite Ed’s resistance, Kate had put him on.

As she watched Harry at the gate, Kate cursed herself for not telling him about Grimes as they were driving up from the homestead. Idiot that she was, she’d been distracted by Harry’s talk of Luca.

Ed signalled for Harry to shut the gate and he did so, hopping on to catch a ride as it swung. The mob flowed out evenly, like water poured from a jug. Ed had taught her that Merinos stay close, in a pretty tight mob, day or night. They stuck together, following the leader, and struck out across the open paddock and off towards the distant trees and the creek. Kate watched them go, so proud of them as they gathered in the dusk at the edge of the paddock. Kate liked this time of day best, with work almost done and the sky a swirl of orange and pink, the dam’s surface a mirror for the vivid colours.

The Woolgrower's Companion

The Woolgrower's Companion