- Home

- Joy Rhoades

The Burnt Country Page 4

The Burnt Country Read online

Page 4

Harry climbed back up to her. ‘Red sky at bloody night,’ he ribbed.

‘Red sky at night,’ she corrected.

‘Shepherd’s bloody delight.’ He laughed.

‘Dad would not have approved of your little variation.’

‘He learnt me.’ Harry laughed again.

Kate smiled. It did sound like her father. ‘Taught, not learnt. And please don’t swing off that trunk, Harry. It’ll come down on you.’ She pointed at the hollow tree trunk halfway up the dam wall, the only shade tree that had been left when the dam was built.

As they walked back to the car, Kate tried to find the words to tell him about Grimes.

‘What’s got ya goat?’ Harry asked as Kate moved the car off.

‘What?’

‘Ya stewin on somethin.’

Kate looked at him.

‘I’m right, eh?’

‘We had a visit today. From your uncle.’

‘Great-uncle,’ he corrected.

Gunner had appeared, to run shotgun alongside the car. He was smart enough not to get hit somehow. He’d be in big trouble with Ed, for disappearing from the muster.

‘So he really is back?’ Harry said.

‘Yeah. He’s working for John Fleming now. On Longhope Downs.’

‘Well, that’s a mistake. What did he want?’

‘He was picking up the wethers I’d sold to Fleming.’

‘Uh.’ Harry lost interest.

‘But also—’

‘What also?’ Harry looked at her.

‘He … He wants you to go and live with him.’ She looked back at him, a boy-man silhouetted against the sky, with the last of the sun draining into the west.

‘He’s in for a disappointment, then,’ Harry said. ‘You told him?’

‘Yes, but—’

‘But?’ Harry said flatly.

‘He insisted. I said we should ask your grandmother. You know, go to Sydney to see her.’ Kate was thinking they’d go soon, to get the trip in before shearing started in just under two weeks’ time.

‘Why the bloody hell’d ya say that?’

‘He’s. He’s—’

‘Dead set on raisin me.’

‘Yes.’

He dropped his head forward, and he was again the small boy who’d come to them years before, tired and alone.

Harry looked up. ‘Smart, eh.’

‘What?’

‘She’s smart, my nan. No flies on the old lady. She knows Grimesy’s a bastard –’

Kate let the swearword go.

‘– an I reckon she’ll be sweet.’ He started to nod. ‘Yeah. I reckon that’s pretty smart of ya. An I get a trip to Sydney!’

She smiled, hoping they were right – for Harry’s sake and for her own.

A little later, back at the homestead, Kate was pleased to see the Rileys’ car coming to a stop outside.

‘Hello!’ She walked down to the fence as Mrs Riley got out of the car.

‘Kate, dear. How are you?’ Mrs Riley smiled quickly, and collected her hat and a small packet from the back seat. Always immaculately turned out, even for an impromptu visit, she was a big lady, both tall and ‘broad of beam’.

‘I do feel terrible, Kate dear, dropping in like this, unannounced, but I was passing and you may need these for the wallaroo.’

Kate accepted what appeared to be three beautifully ironed pillow cases, slightly worn but pressed, with a faint scent of starch.

‘Harry told us that you might be short of cases for him to sleep in? I thought I’d best drop them off. They were destined for the ragbag, otherwise.’

‘Thank you.’ Kate smiled at her. ‘Harry will be pleased. But please do stay for a cup of tea?’

‘Truly, I shan’t, dear. I am already intruding.’ She kissed Kate farewell, removed the hat, placed it on the back seat and departed.

Kate had no choice but to wave her off.

Just over an hour later, Kate stood with a mug of tea, the verandah upright post still warm against her back, and watched the sun sink from a clear sky into the Amiens hills. The pasture dried out a little more, every week without rain. It was not yet a drought sort of dry. But bushfire-dry, for sure.

Outside the homestead fence, Gunner paced, pleading with her. Ed would have one of the boys feed all the dogs soon, but Gunner always tried his luck at the homestead anyway.

‘You can go on your way, my friend,’ Kate called to the dog. ‘Nothing for you here.’

As she sipped her tea, something smallish and dark that looked like a chop bone sailed over the fence from behind the house, landing just beyond the dog. Another followed, and Gunner was on them in a second.

‘Harry!’ Kate called. There was silence, and no more bones.

Her crossness was interrupted by headlights from an unknown car poking up out of the gully. With Amiens and all on it pariahs in the district, they got no casual callers. Had Jack come back? Her fear was automatic. But this couldn’t be Jack; he’d be driving fast, and she suspected he was gone now from the district. For a bit, anyway.

Kate hurled the remnants of her tea onto the garden and put the cup in the kitchen. She wanted to be back out on the verandah, three feet above the visitor, when whoever it was arrived. Home pitch advantage.

But then she saw. The verandah steps would be no help with this visitor.

It was Luca.

CHAPTER 6

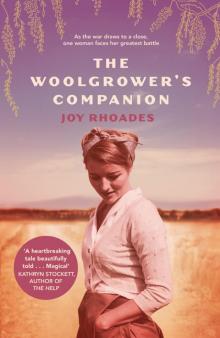

While the greatest regard for animal husbandry is an essential, on no account shall the woolgrower allow vestiges of endearment to impede his clarity of purpose. A hapless poddy lamb, hand-raised but long since weaned and put out to pasture, must nonetheless be culled when its time encroaches.

THE WOOLGROWER’S COMPANION, 1906

In the twilight, Luca got out of the Rileys’ car and straightened up, putting a hand through that thick black hair. He was just the same: her height but broad, his face a rich brown, deepened by his work in the sun. She knew all of him, from how he moved and how he felt, even down to the scar ridges on his back.

He closed the gate behind him and glanced around. Harry must have told him about the wallaroo.

From the lawn, he looked up at her, taking her in.

‘Luca,’ she said.

He almost smiled.

Kate had to be sensible, and to breathe. She wanted the security of the kitchen, the bustling calm of Daisy. ‘Come in.’ Her traitorous voice was hoarse.

In the kitchen, Luca stood looking at her across the expanse of the table. Up close, he was the same too. A little older, some flecks of grey in his hair, yet the same handsome Luca, with those pale green eyes and milk-tea skin. Her hand went to smooth her hair, and his eyes followed. He smiled again. They knew each other so well that she felt a physical pain in her chest. This would be much harder than she’d imagined.

Embarrassed, she sat down. Luca sat too, and his familiar scent wafted over to Kate: soap, and sump oil, and him.

Daisy bundled in from the laundry and he was on his feet. ‘Mister Luca!’ She grinned, as pleased as he was. ‘Pearl! Pearl!’ Daisy called. ‘I get her for youse,’ she said, disappearing again into the hall.

The silence pressed on Kate as they looked at each other across the kitchen table, Luca smiling, Kate anxious.

Then Daisy was back, carrying a bathed Pearl in pyjamas, and she shuffled the still-damp toddler into Luca’s arms.

‘S’Luca, eh, littlie? He know youse forever. Since you was born.’ Daisy beamed at them both.

Pearl didn’t take to strangers, usually. But she just sat in Luca’s arms, thoughtful, observing him and her mother’s smiling face. Then Pearl reached out and patted Luca’s head as if he were a dog. Daisy and Luca laughed. Pearl’s fingers dropped to touch the beads of perspiration on his forehead. ‘Wet,’ she said to her mother.

Daisy laughed again and took the toddler back. ‘Bed, Pearl, now.’

Luca wiped his forehead with the back of his hand. Kate hoped Daisy would put Pearl to bed and return to them, but there was an unusual silence in the house.

Mrs Walters appeared then, all bright eyes and neat curls.

‘Our new housekeeper. Mrs Walters,’ Kate said.

Luca dropped his head briefly and smiled.

Kate had forgotten that. His way of greeting. ‘This is Luca Canali. He worked here. During the war. He’s a POW. Was. Was a POW.’

‘Before,’ he said. ‘Now I work at Mr Riley.’

‘How do you do,’ Mrs Walters said politely, then disappeared into the hall again. In the silence, the kitchen clock ticked on, and Luca seemed not the slightest bit uncomfortable, happy to look at her.

Kate started to shift in her chair. Where was Harry? Missing. Had he known Luca was coming?

He startled her when he spoke. ‘Perhaps out, Signora? It is possible?’ It was his voice this time that was hoarse.

The house seemed too quiet after all. They went onto the verandah, and Kate sat, immediately wishing she hadn’t, as Luca stayed standing. She had a sudden irrational terror that he was leaving. Then he spoke.

‘You are good.’

‘Yes. Well. Thank you.’ But Kate realised then it was a statement, not a question. She was an idiot. She pulled at the rattan of the chair seat, and then stopped herself.

Luca walked to and fro on the verandah and she was fearful of her pleasure at the sight of him.

‘Before, in August, I come back,’ he said, waggling his head, trying to start.

‘You did,’ Kate said softly. He must hear the regret.

She didn’t ask about his family. Harry had told her bits already. Both Luca’s brother and father were dead by the end of the war, his sisters married and settled. There’d been little to keep him in Italy. He’d accepted the Rileys’ invitation to sponsor

him. So here he was. What Harry had not said – and what Kate had not asked – was whether he was married. Please God, let there be a wife. But he wouldn’t be here if he had a wife.

She wondered if it was Jack’s appearance that had prompted Luca to come and see her. Jack would be staying at his mate Biggsy’s pub; the whole town must know by now Jack had left her for good.

‘I come back. I hope …’ As he walked, his voice trailed off and he couldn’t finish. Eventually, he stopped pacing and stood on the edge of the verandah, looking out across Amiens. ‘Much grass,’ he said.

‘Three good years of rain since you’ve been gone.’

He nodded, impressed, as though Kate had conjured up the rains.

‘It’s drying out now though.’

‘Sì.’ He could see that.

He came then to stand beside her.

She tensed, not wanting him to be so close. ‘You were kind to buy the Meccano for Harry.’

‘Yes. Mrs Riley, she go in the shop for me.’

Kate looked at him.

‘Mr Nettiford not like the Eye-ties. He explain me.’

Poor Luca. He would get a lot of that in town. Even the boom times since the end of the war – it was hard to get workers to fill all the jobs going in Longhope – had not erased the way Australians felt about the Italian immigrants. Foreigners were bad enough, but former POWs were the worst of the lot.

‘After, Mrs Riley, she buy for me.’

That sounded like her. A silence passed between them. Not uncomfortable, within reach of each other, their eyes on Amiens.

It made Kate remember their days at the end of the war. Each night Luca would come, bringing her a meal that the other POW had cooked for them all. They would eat together, in the Amiens kitchen, just the two of them alone in the homestead in gentle and remarkable domesticity. Then Luca would stay. They would make love. All for a few short, glorious days. What madness was that?

‘Today I come to you,’ Luca said. He took her hand in his and the heat of his fingers sent something through her. His eyes serious, he leant in, his mouth towards hers.

Kate pulled away.

Luca stopped still, his eyes on hers, but she got up, pushing past him.

‘Signora?’

Kate suddenly felt the weight of what she had to do and dropped back into her chair. No matter that it was the right thing, the best thing, the only thing, despite the pain it would cause him.

Luca walked – paced – in front of her, hands behind his back, eyes on the verandah boards. She knew him so well, his gait, his smile.

He stopped pacing and looked at her. ‘I know, Signora. Your wedding – it is dead.’

She looked away, ashamed.

‘I am sorry for this,’ Luca said. Suddenly, he pulled the other wicker chair up close to hers and sat. He took her hands, their faces only inches apart. ‘I am sorry, yes. But happy. For me.’ Luca spoke intently, the roughness of his fingers firm around her hands.

Dear Luca. She extracted her hands gently and stood up.

But he kept speaking. ‘I say you, Signora – Kate – I ask you.’ He stopped and thought again. ‘I ask you. To marry. After. Soon.’

She shook her head, very slowly. She willed, willed, willed herself not to cry, and she shut her eyes to hold in the tears.

‘You think on this?’ Luca said with panic. He was watching her – she knew it.

She shook her head again. Then she spoke, hearing her voice sounding old. ‘I’m not going to get married, Luca.’

‘I wait.’

‘It’s not that.’ Kate hated herself. She’d never imagined he would come back. She opened her eyes, the disloyal tears in check.

‘It is me.’ He looked stricken, as if he’d expected that she might say no. ‘I have nothing. Not the land. But you?’ He spread his arms and caught all of Amiens.

‘No, no. It’s not that. I just can’t. I’m a bad wife.’

‘Perhaps, to Jack.’ He shrugged. Jack deserved it, he seemed to say.

She shook her head, sadness crushing her. ‘I have responsibilities, duties to Daisy and to Pearl. I have to protect them.’

He looked at her, puzzled. She watched him wrestle with the realisation that she was serious. ‘We’ve managed so far, you see? The Board has not been able to take Daisy or Pearl. But it will always be a struggle, especially if – when – Jack divorces me. They will argue I’m unqualified. Unfit.’

She looked down. In her heart, she didn’t feel like a bad woman. But if everyone believes something, how is it not true?

‘The local businesses too. Those men continue to deal with me, grudgingly. That will change after a divorce, let alone a remarriage. I’m a woman running a place on her own. That alone is not the done thing. I’ll be punished, you see.’

He shrugged. ‘I help this. Much help to you.’

‘I know. You would. But I still can’t marry you,’ she said simply. ‘Or anyone.’ Those words then were a kind of weight off her.

Kate felt herself on the edge of a huge sea, as the ebb began and all of the power and strength that was Luca began to draw away from her. ‘You think I’m a coward,’ she said.

He waggled his head once, slowly, sadly. ‘No, not vigliacca, Signora.’

‘It might seem silly. But I have to look after Daisy and Pearl. It’s a duty.’ She was embarrassed to use the word to a former soldier.

Luca said nothing for a moment. ‘There is other duty also. I know this,’ he said softly. He took her hand and placed her palm flat on her sternum, and she felt her own heart beating hard within her chest. The heat of his fingers on her hand shot through her. ‘Your duty to you.’

She shook her head and tears fell from her eyes. Then, finding strength, and with trembling fingers, she gently removed his hand.

Luca turned and looked out across the paddocks, not wanting her to see his devastation.

They stood for a long moment like that, each with their own grief.

Luca nodded. ‘I go,’ he said, his voice thick.

She could not speak for fear of breaking down. But she knew she was right.

Kate watched him walk away through glassy tears with the same terrible sense of loss she’d felt when he got on the POW train to leave the district at the end of the war. Then she’d truly believed she’d never see him again. And the pain burnt.

CHAPTER 7

It was written by those most observant of Englishmen, our earliest explorers, that frequent conflagrations were undertaken by the Aborigines, the smoke and cinders visible for many miles.

THE WOOLGROWER’S COMPANION, 1906

Kate pulled herself through the days by force of will. She knew that she’d had to reject Luca. She was convinced it was the right thing. But she’d think of him, and immediately of her loss. Their loss.

By the third day, Saturday, she felt something, a change in herself, like a snake sloughing off an old skin, doing what was necessary to survive. She got herself ready for the day’s burning off, and accepted a cup of tea and some toast from Mrs Walters. But weariness lingered.

Kate usually liked to be about in the paddocks first thing, in the cool of an early morning. But not today, for some reason. She told herself it was just tiredness, as she walked in the paddock with the Amiens men around her. She was worried about what they had to do, worried that it would go wrong. At least she was ready: a scarf at her neck for the smoke, the fire-beater in her hand. The beater was a feeble thing, really, but better than nothing: a long shovel handle with a flat canvas flap attached, the canvas measuring a foot by a foot, a quarter of an inch thick.

Ed walked in front, carrying a metal fire torch as well as his beater. Harry, and the stockmen Robbo, Johnno and Spinksy, followed behind. Kate worked to keep up. She was almost woozy with tiredness.

Ahead of them all was a planned burn-off in Deadman’s paddock. It ran parallel to the creek that divided Amiens from her difficult neighbour, John Fleming on Longhope Downs. A double hex of sorts, if Kate thought about how dry it was.

Ed stopped them at the edge of the flat by the creek, and they formed an odd semi-circle around him, ready for instructions.

The Woolgrower's Companion

The Woolgrower's Companion